A rhizome is a term used in biology & botany that refers to a subterranean plant stem that sends out roots and shoots from its nodes. More broadly, it can refer to a structure characteristic of many plants and fungi. A rhizome is a horizontal, decentralized system: it can grow from any point and shoot off into separate rhizomes, meaning it’s not bound to a specific plant or tree. Rhizomes can connect to other root systems. Deleuze & Guattari introduce their concept in A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1980). Their writing is very complex and often incomprehensible, so it will be tempting to ignore the more obscure parts of the discussion and use the rhizome as a simple metaphor, but Deleuze dislikes metaphors. And getting used to their way of writing can be extremely rewarding.

Let us now proceed the way they do: first by determining the oppositions of the concept. First, let’s determine what the rhizome is not. The primary concrete example D&G use is the book:

A first type of book is the root-book. […] This is the classical book, as noble, signifying, and subjective organic interiority (the strata of the book). […] The law of the book is the law of reflection, the One that becomes two.1

The root-type book has an organic unity similar to the tree structure. This “one becomes two” principle describes that structure: the trunk, then two branches, then two more branches from each, and so on. The borrowed terminology we use in philosophy is also evidence of the primacy of the tree in classical thought:

It is odd how the tree has dominated Western reality and all of Western thought, from botany to biology and anatomy, but also […] all of philosophy: the root-foundation, Grund, racine, fondement.2

The primary example of this in philosophy would be Plato’s forms: There is the ideal form (the foundation), and then there are imperfect instances of actual objects that try to represent or imitate that form as closely as possible. The actual instances will never perfectly fit the concepts they’re trying to signify, so any actual instance is somehow lacking.

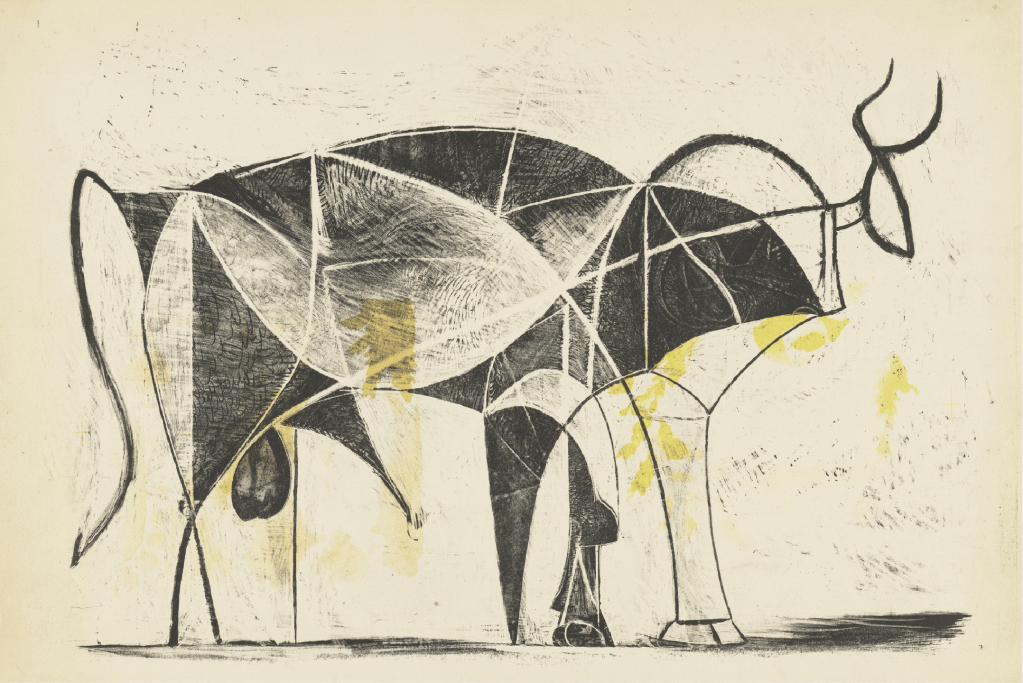

In art, this hierarchy was shattered first with challenging realism as a value and then with non-representational painting. For example, Pablo Picasso’s bull drawings, which try to get farther and farther from the form of the actual bull, challenge the idea that the more closely a painting resembles that which it is trying to represent, the better.

There is also completely non-representational painting. This type tries not to imitate but to ask: what can painting do?

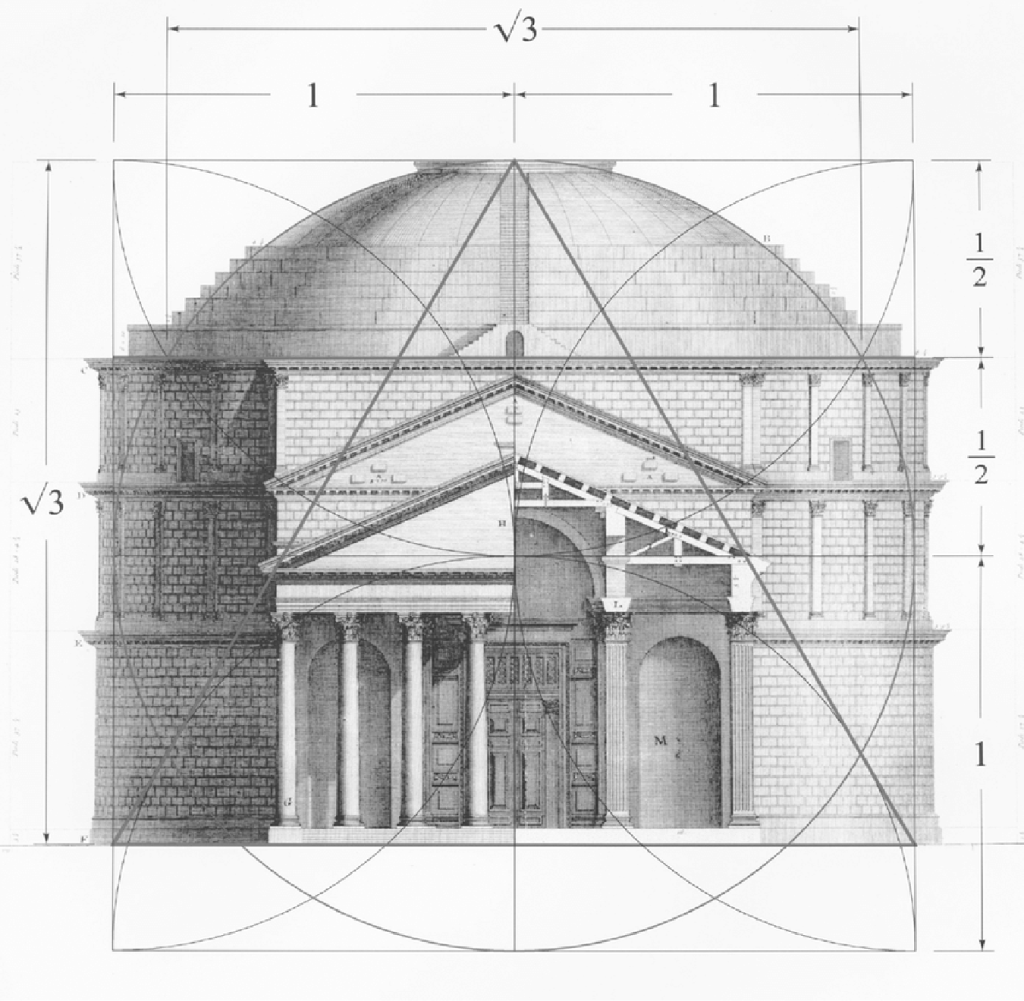

If what Deleuze calls arborescent thinking is representational, an example from architecture of that would be the buildings of Andrea Palladio: in search of perfect proportion, as if there is an ideal form of the building, which is all alluded to in the title of Colin Rowe’s famous essay.3 A more crass example would be buildings that try to look like something, to represent something directly.4

Like non-representational painters and avant-garde architects, D&G are challenging the primacy of the arborescent, the hierarchical mode:

We’re tired of trees. […] All of arborescent culture is founded on them, from biology to linguistics.5

There is also the radicle system or the fascicular root (in biology, a bundle of leaves or flowers growing crowded together). In the case of the book, an example D&G give is William Burroughs’ cut-up method, where there is a unified structure behind fragmented bits of text. Nietzsche and Joyce also fall into this category, not breaking with the binary system completely.

A strange mystification: a book all the more total for being fragmented.6

After D&G have distinguished the root-system and the radicle system from the rhizomatic one, on page 6, we find the first mention of the rhizome:

The multiple must be made, not by always adding a higher dimension but …with the number of dimensions one already has available—always n-1 (the only way the one belongs to the multiple: always subtracted). Subtract the unique from the multiplicity to be constructed: write at n-1 dimensions… A system of this kind would be called a rhizome.7

Maybe n-1 refers to removing oneself from one’s writings because they mention the unattributability of the book and how the book has no subject or object. Similar to the death-of-the-author arguments made by Bathes.7 But subtracting the unique might point to a different explanation: getting behind the apparent self-sufficiency of an actual event or object, stepping back from the concrete detail, and seeing it in the web of relations it exists in. For example, instead of seeing rats as separate organisms, we might see them unabstracted from the air they breathe, the shadows they cast, the relationships they form, the ways they move, and the garbage they eat.

It’s clear, then, that not just potatoes and crabgrass are rhizomes. Rat burrows, ant colonies, vernacular cities, musical forms, the movement patterns of tourists, a pool of oil on a pan, a group of guerrilla fighters, and the unconscious are also rhizomes. Even the book—A Thousand Plateaus—is a rhizome.

Since D&G feel that this is not enough, they then present six characteristics of rhizomes:

1 and 2: The Principles of Connection and Heterogeneity: The ‘pure’ rhizome is infinitely connectable, with each point having the capacity to connect with any other point in any other system. A pure mechanism or machine operates on a plane of consistency that is not immediately apparent and will become perceptible after we follow the rhizome down to the most abstract connections.

A rhizome ceaselessly establishes connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences, and social struggles.9

The example they use here is language:

It [language] evolves by subterranean stems and flows, along river valleys or train tracks; it spreads like a patch of oil.10

3: The Principle of Multiplicity: The multiple must be treated as a substantive, it cannot be reduced to the multiple either. Here we get example of the puppeteer:

Puppet strings, as a rhizome or multiplicity, are tied not to the supposed will of an artist or puppeteer but to a multiplicity of nerve fibers, which form another puppet in other dimensions connected to the first: “Call the strings or rods that move the puppet the weave. It might be objected that its multiplicity resides in the person of the actor, who projects it into the text. Granted; but the actor’s nerve fibers in turn form a weave. […]”11

What does it mean to treat the multiple as a substantive? To treat many things as really many. To forget the subject and the object, to forget unity. To think of only lines, not points or positions in relation to the whole.

4: The Principle of Asignifying Rupture: Any rupture is not going to destabilize it. The rhizome has no beginning and end, only a middle (milieu) from which it grows and overspills. It proceeds by the conjunction ‘and…and…and’…

A rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or new lines. You can never get rid of ants because they form an animal rhizome that can rebound time and again after most of it has been destroyed.12

This applies to American and some English literature: such works do not follow conventional narratives but move from one episode to the next. Joyce seems to fit, and maybe Beckett. The entire rhizome cannot be traced back to a single origin. Saying that rhizomes do not have a single point of resolution necessitates that we stop thinking with foundational concepts that attempt to explain everything:

A rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo. The tree is filiation, but the rhizome is alliance, uniquely alliance. The tree imposes the verb “to be,” but the fabric of the rhizome is the conjunction, “and… and… and…”13

Perhaps, here it would be helpful to think of the difference between a rhizome and a hydra: the hydra grows two heads when one is cut off, while the rhizome can give birth to separate entities. Hydras are arborescent.

A very vivid example D&G use is that of the wasp and the orchid. To understand this, we have to go through some biology: In simple terms, a pollinator animal moves pollen from the male anther of a flower to the female stigma of a flower. Pseudocopulation is a behavior that takes place when a pollinator attempts to copulate with a flower that looks like a female mate. The wasp orchid, or Chiloglottis, is a flowering plant that looks much like a female wasp and is pollinated by thynnid wasps.

Wasp and orchid, as heterogenous elements, form a rhizome. It could be said that the orchid imitates the wasp, reproducing its image in a signifying fashion […] At the same time, something else entirely is going on: not imitation at all but a capture of code […]14

Another example is that of a virus that transmits from one species to another (from the baboon to the cat) and brings a trace of the DNA of the former. Phenomena like this ought to make us dispense with arborescent schemas for evolution:

Evolutionary schemas would no longer follow models of arborescent descent going from the least to the most differentiated, but instead of a rhizome operating immediately in the heterogeneous and jumping from one already differentiated line to another. Once again, there is aparallel evolution, of the baboon and the cat; it is obvious that they are not models or copies of each other […] We form a rhizome with our viruses, or rather our viruses cause us to form a rhizome with other animals. […] The rhizome is an anti-genealogy.15

5 and 6: The Principles of Cartography and Decalcomania: Its trajectory is mappable, but not traceable. An image of a rhizome does not let us know its trajectory. An example of the traceable is psychoanalysis, which has a theory set in stone, a theory to which all the facts of the matter have to be morphed to fit and confirm it.

It [psychoanalysis] consists of tracing, on the basis of an overcoding structure or supporting axis, something that comes ready-made.16

The map is open and connectable in all of its dimensions; it is detachable, reversible, susceptible to constant modification. It can be torn, reversed, adapted to any kind of mounting, reworked by an individual, group, or social formation. […] Perhaps one of the most important characteristics of the rhizome is that it always has multiple entryways: in this sense, the burrow is an animal rhizome …17

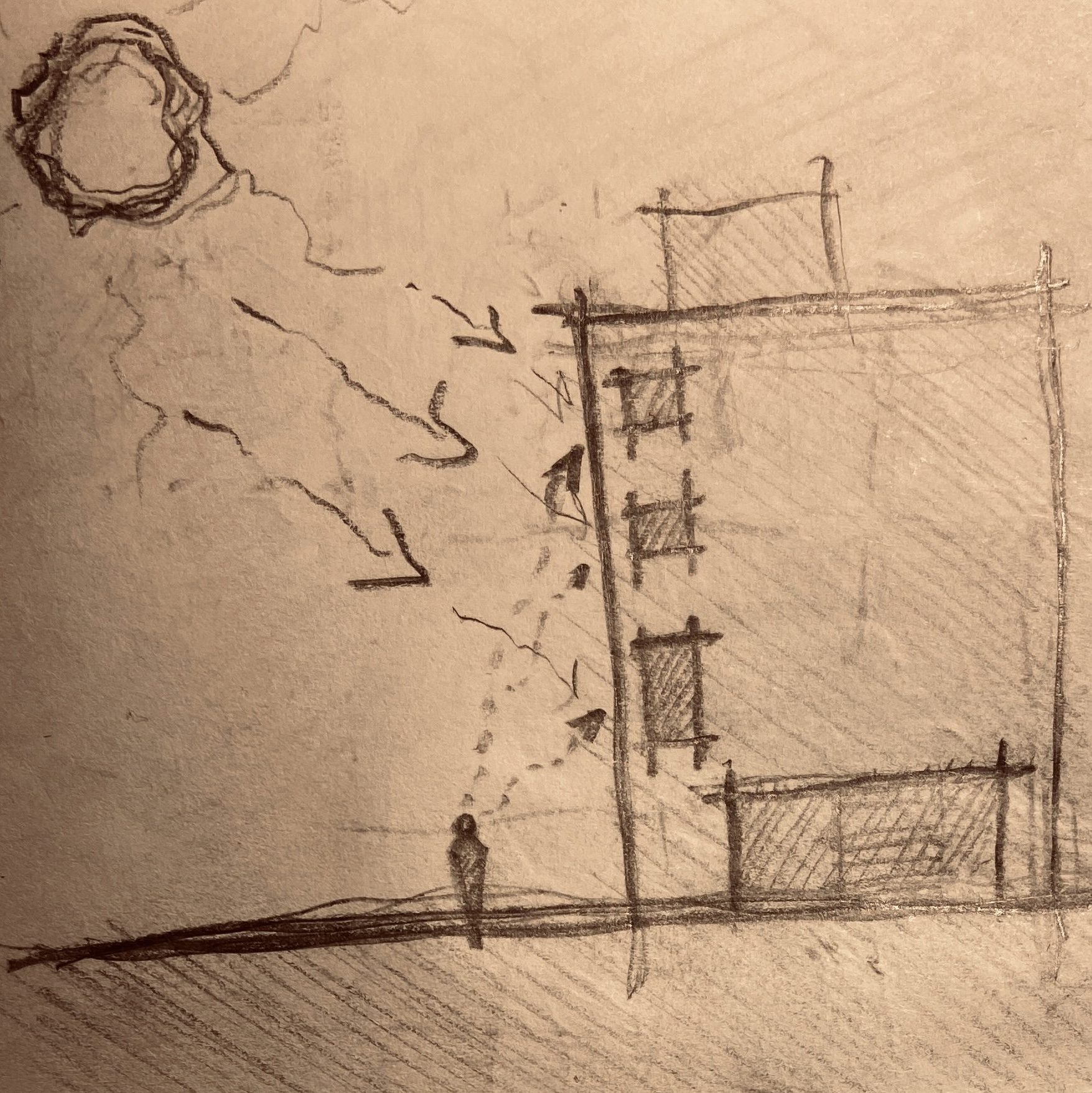

Grassroots, ants on the march, rats building burrows, and guerrillas operating in enemy territory do not follow simple binary choices or directions laid out in suggested routes. Guerrilla fighters or tourists use maps, but they do not always stick to the prescribed routes or tracings. Rhizome as a map offers more possibilities than the already specified ones.

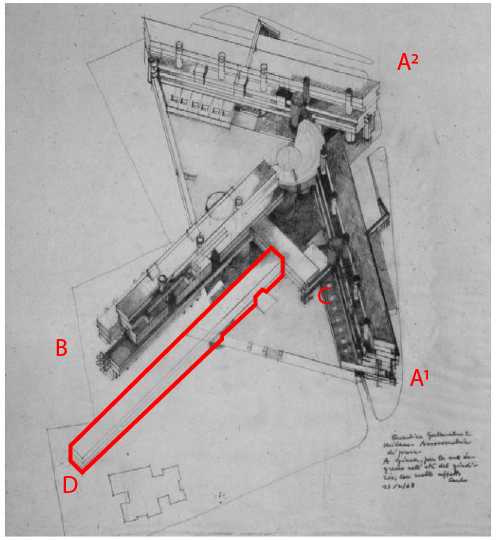

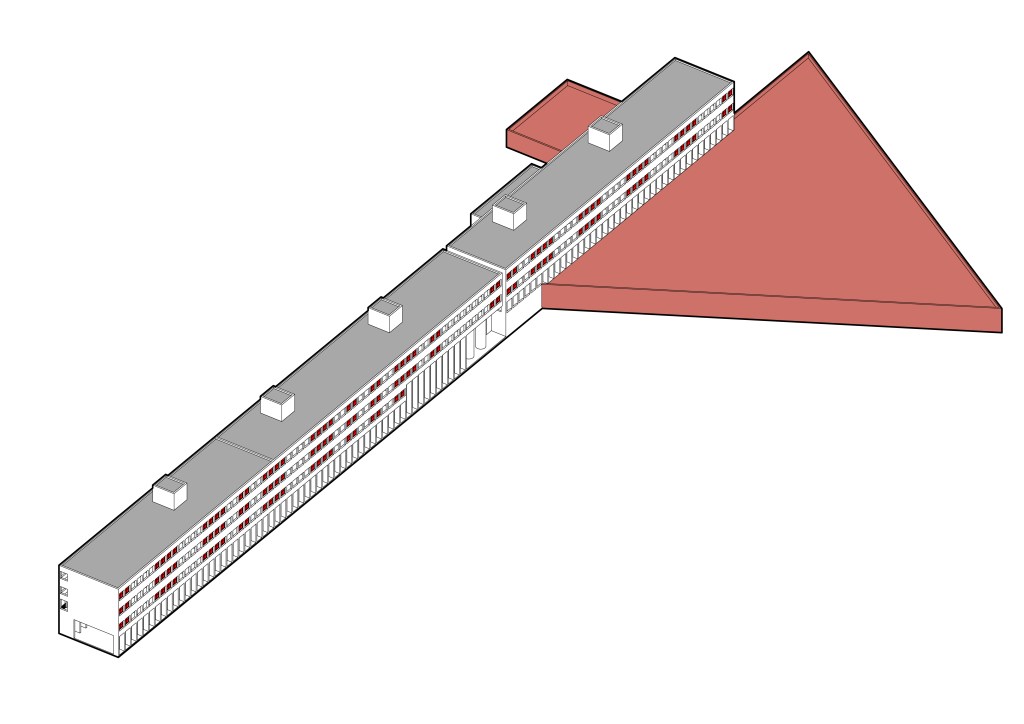

The urban planning ideas of the Garden City Movement and Le Corbusier are also examples of this rigidity determined in advance by an overcoding structure, which contrasts with the city of Amsterdam, further exemplary due to its underground system of stem-canals.

With that, D&G get to the end of the discussion without mentioning fungi, an example used frequently today.

All this reads like a manifesto for non-linearity in theory and practice, as an account of what might be possible, which is why the chapter ends with calls to action:

Write to the nth power, the n – 1 power, write with slogans: Make rhizomes, not roots, never plant! […] Have short-term ideas. Make maps, not photos or drawings. […] establish a logic of the AND, overthrow ontology, do away with foundations, nullify endings and beginnings.18

References

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press. p. 5

↩︎ - Ibid., p. 18 ↩︎

- Rowe, C. (1982). The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays. MIT Press.

↩︎ - How Not to Do Things With Buildings ↩︎

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press. p. 15 ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 6 ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Barthes, R. (1977). Image, Music, Text. Fontana.

↩︎ - Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press. p. 7 ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 8 ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 9 ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 25 ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 10 ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 10-11 ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 12 ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 24-25 ↩︎