I’m proposing a different weapon in the designer’s arsenal – a solution to the problem of pointless collection and endless browsing. To explain the problem and the weapon, I will use the work of Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, Niklas Luhmann, and Roland Barthes.

Architecture, like any other art form, is intertextual: a building does not stand alone and is not experienced as separate (Kristeva, 1982, p. 66). It does not arise out of the pure creativity of the author: analogous to a text, a building is not like “a line of words releasing a Single “theological” meaning (the “message” of the Author-God) but a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash” (Barthes, 1977, p. 146). Each of its elements has precedents. Its form is a copy. Its function is nothing new. Its context is all too familiar.

While this may be obvious, most architects try to escape this inescapable bind. They try to make their buildings stand out for the sake of standing out. They fertilize them with symbols, fatten them with useless originality, only to get a chimera of copies, since “all this creative power of the mind amounts to no more than the faculty of compounding, transposing, augmenting, or diminishing the materials afforded us by the senses and experience” (Hume, 1748/1907, p. 16).

I’m proposing the opposite. Let us embrace this bind rather than fight it. Why not distill what gets copied, what repeats, and what finds a use half-irrespective of the situation? We do this already when we save different architectural projects, look for inspirations on social media, try to find what to mimic from a famous work, write down a specific regulation we don’t want to forget, etc. So the question is not of general value. The question is how to make this process more (un)systematic.

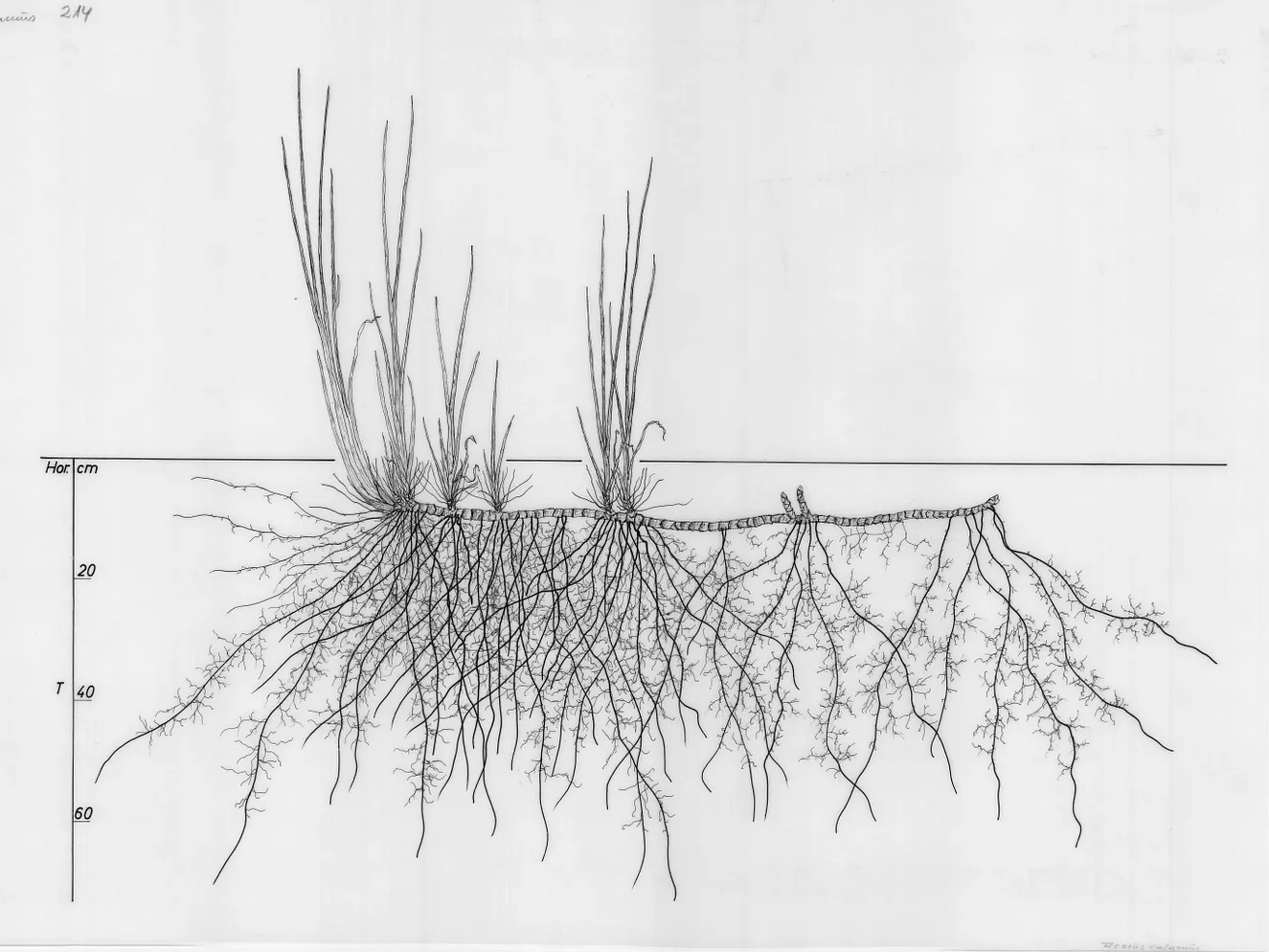

Enter the rhizome: “Subtract the unique from the multiplicity to be constituted; write at n – 1 dimensions. A system of this kind could be called a rhizome. A rhizome as subterranean stem is absolutely different from roots and radicles. Bulbs and tubers are rhizomes. Plants with roots or radicles may be rhizomorphic in other respects altogether: the question is whether plant life in its specificity is not entirely rhizomatic. Even some animals are, in their pack form. Rats are rhizomes. Burrows are too, in all of their functions of shelter, supply, movement, evasion, and breakout. The rhizome itself assumes very diverse forms, from ramified surface extension in all directions to concretion into bulbs and tubers. When rats swarm over each other. The rhizome includes the best and the worst: potato and couchgrass, or the weed. Animal and plant, couchgrass is crabgrass” (Deleuze & Guattari, 2003, pp. 6-7).

To understand the rhizome, we must explain its binary – we must explain what it contrasts with. The two main differentiating characteristics of a rhizome are (1) connection and (2) heterogeneity: “any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be. This is very different from the tree or root, which plots a point, fixes an order” (Deleuze & Guattari, 2003, p. 7). The rhizomatic structure stands in sharp contrast to an arborescent one. A tree, for instance, has a hierarchical body: there is a clear order and rule according to which a specific part of a tree connects to another. Much philosophical thinking procedes in the same manner, but as in a philosophical work, so in a design archive, we may opt for Adorno’s formula: “In a philosophical text all the propositions ought to be equally close to the centre” (Adorno, 2005, p. 62).

A hierarchical structure has an order before the elements are collected. The author imposes an artificial and readymade system that filters the parts into different enclosures. All the “inspiration” material for building exterior design goes into one space; all fire safety principles go into another. The problem is that this type of system cannot communicate with its author – it cannot surprise you.

By contrast, a more fluid structure can give rise to new information through unexpected connections: “It is impossible to think without writing; at least it is impossible in any sophisticated or networked (anschlußfähig) fashion. Somehow we must mark differences, and capture distinctions which are either implicitly or explicitly contained in concepts. Only if we have secured in this way the constancy of the schema that produces information, can the consistency of the subsequent processes of processing information be guaranteed. And if one has to write anyway, it is useful to take advantage of this activity in order to create in the system of notes a competent partner of communication. […] If a communicative system is to hold together for a longer period, we must choose either the rout of highly technical specialization or that of incorporating randomness and information generated ad hoc. Applied to collections of notes, we can choose the route of thematic specialization […] or we can choose the route of an open organization” (Luhmann, 1992, pp. 53-61).

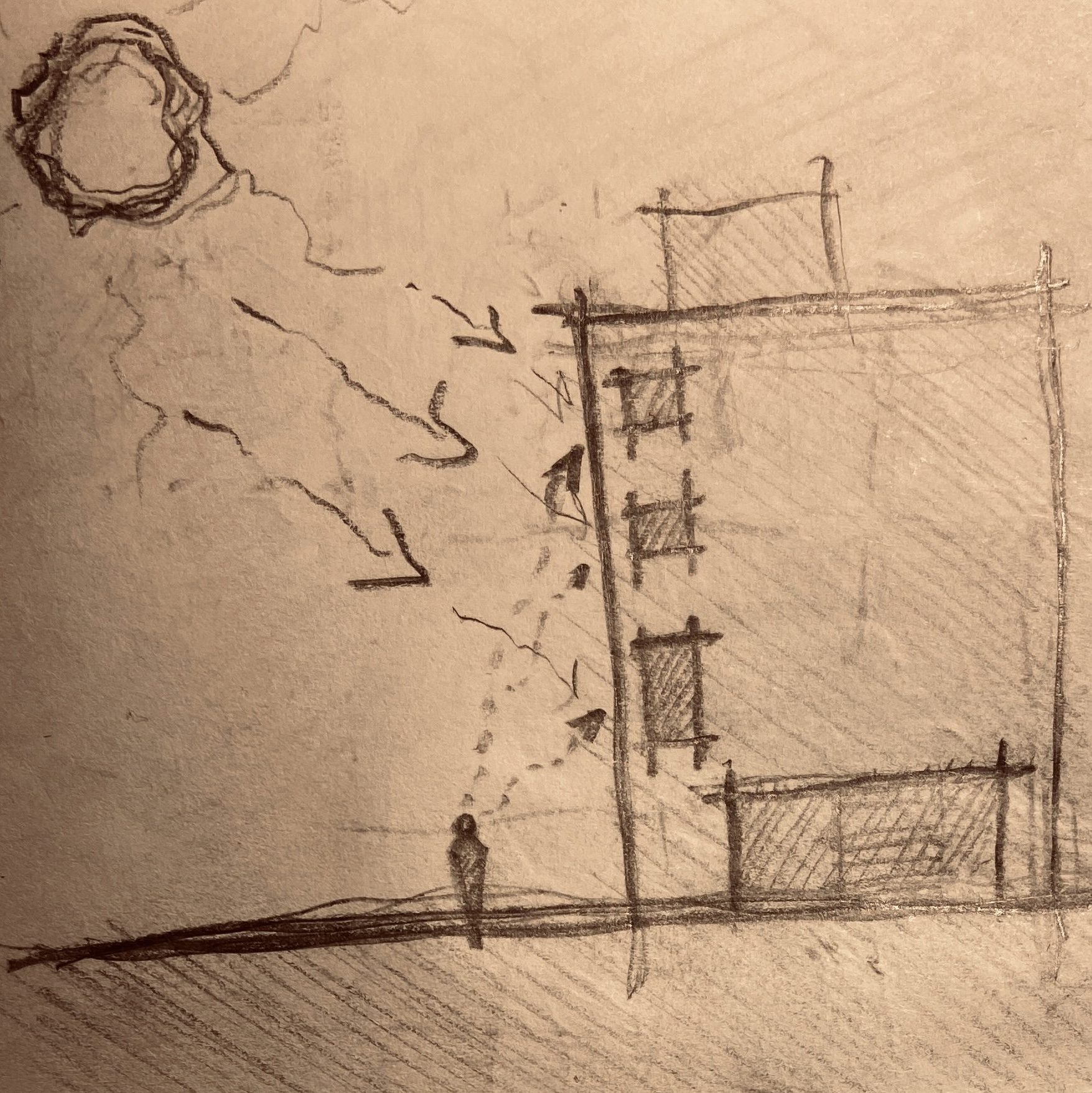

Like crabgrass, any node of a rhizomatic archive can expand upwards. The non-hierarchical structure does not dictate the places of expansion and decay; they instead arise out of necessity at any given time and place. Any part of the archive has the potential to grow, to intensify, irrespective of its preconceived importance.

A horizontal, rhizomatic structure of grass that can grow vertically at any point.

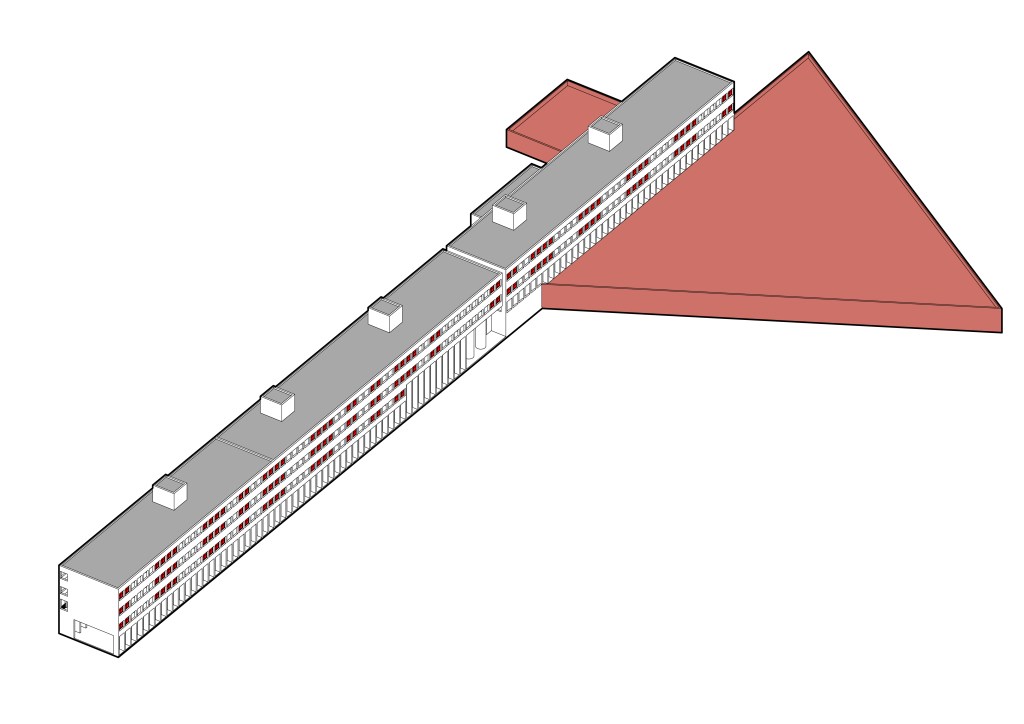

Connection and heterogeneity are the primary characteristics I demand of a design archive. The archive can be physical or digital, singular or dispersed, but chaos must engulf it: a principle for arranging duplexes in an apartment building stands next to a specific design for the first step of a staircase; data on the relative dangerousness of one-way streets follows the phenomenological exploration of shadows in Japanese architecture.

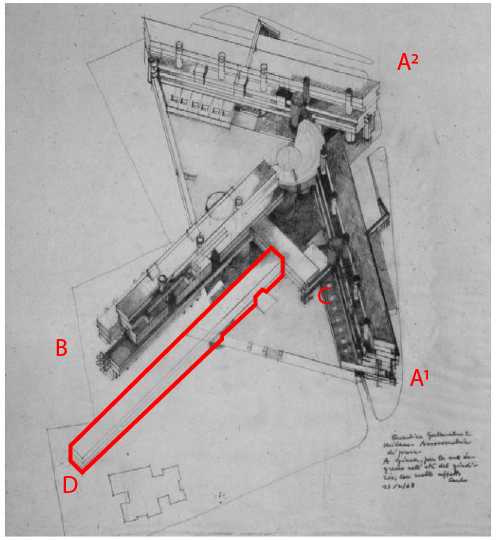

In concrete terms, let’s imagine this rhizome as a physical notebook. Each principle/element/note has a unique identifying number. The final page has a table of contents that starts from the bottom and is written in reverse. The notes have other numbers listed on the bottom, signifying the related elements. Once the notes meet the table of contents, the notebook ends, and another begins. So, one may suddenly see, for instance, the connection between a specific approach to the placement of trees near streets and the arrangement of shading elements in an open corridor.

The proposed alternative to endless browsing and collection of material in an arborescent manner, then, is a rhizomatic collection of disparate but densely linked elements. One does not worry about order, one lets the machine operate, one forgets its mechanism, and the structure arises in medias res.

References

- Adorno, T. (2005). Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life. Verso.

- Barthes, R. (1977). Image, Music, Text. Fontana.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (2003). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Continuum.

- Hume, D. (1907). An enquiry concerning human understanding; and Selections from a treatise of human nature. La Salle, Ill. Open Court Pub. Co. (Original work published 1748)

- Kristeva, J. (1982). Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art. Columbia University Press. p. 66.

- Luhmann, N. Kommunikation mit Zettelkästen. Ein Erfahrungsbericht. in. André Kieserling (1992). Universität als Milieu. Kleine Schriften. Haux. Bielefeld. pp. 53-61.